Khaled Hosseini’s third novel strikes universal chords.

A crowd mobbed BookPeople, Austin, Texas, for Hosseini’s recent appearance.

And the Mountains Echoed by Khaled Hosseini

Riverhead Books (Penguin Group ); 404 pp., $28.95 hardback. Also available in paperback (Bloomsbury Publishing), Kindle, Nook, Audible, audiobook CD, SoundCloud, iTunes, and large-print (Thorndike Press) editions.

Guest Review by Lanie Tankard

“…and the place echoed every word,

and when he said ‘Goodbye!’

Echo also said ‘Goodbye!’”

—Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book III (Trans. by A.S. Kline)

Khaled Hosseini took a risk in his third novel. He tried a different structure.

Khaled Hosseini took a risk in his third novel. He tried a different structure.

In his first published work, The Kite Runner, Hosseini followed one boy’s life and how it related to his childhood friendship with another boy named Hassan, portrayed through the voice of the protagonist named Amir.

In his second novel, A Thousand Splendid Suns, Hosseini focused initially on the individual stories of two women, Mariam and Laila, and then later on both as their paths crossed. I admired the fact that, being a male author, Hosseini had pulled off a convincing protagonist gender shift from his first book.

When I recently heard Hosseini discuss his third book, And the Mountains Echoed, he noted, “The structure of this novel was far more ambitious.” He addressed a packed crowd in Austin, Texas, at BookPeople, which was already mobbed an hour before Hosseini was scheduled.

“The heart of the book is about an act of separation—a relationship between a boy and his sister,” he told us, after reading an excerpt. “Splitting them affects who they become as adults,” as the boy has been “almost like a parent to her.”

Hosseini offered details about how he shaped the book.

“Like a giant oak tree, there’s a trunk to the novel that branches out with all the characters, and the geography of the settings as well. It gets wider as the book goes on,” he said. “It was the hardest book to write.”

And it was the hardest book to read, at least for me. As if traveling on the ancient Silk Road, many characters in Mountains Echoed take circuitous routes to their ultimate destinations—and so does the storytelling. These interwoven lives begin to resemble the stacked “spaghetti bowl” of an interstate highway with flyover ramps and exits.

Such a plot construction is not necessarily detrimental to a story, though, nor to one’s growth as a writer. Once again, I admire Hosseini for stretching himself rather than relying on the formulaic repetition of a style with which he’d become comfortable.

In Mountains Echoed, Hosseini constructs the metastories of an entire clan to examine their intersections. It becomes an interesting device for disentangling the relatives in a particular family of origin as they fan out across the globe. Hosseini investigates the genealogical ramifications of family connections. He scrutinizes various generations as if he were peeling back delicate paper-thin layers of phyllo from a wedge of baklava with tweezers.

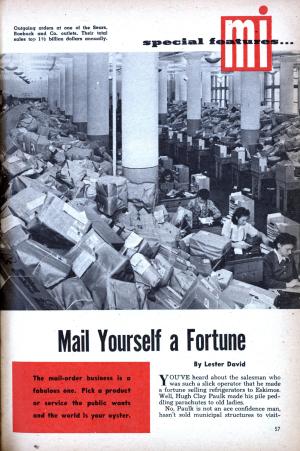

Charting the novel’s cast

Lanie Tankard’s aide-memoire—her cheat sheet for the novel.

I did have to chart my way through the book, however. Early on, I had the fortunate premonition to start drafting a map to follow as I read. I wonder why the editor didn’t suggest inserting a family tree to assist the reader? Yet quite honestly, the lack of one did not deter me from being totally absorbed by this story, even though I did have to consult my hand-drawn legend from time to time to keep the characters straight.

Hosseini’s storytelling ability is nothing short of mesmerizing. He knows just when to stop with a particular strand, leaving the reader hungering for more detail. He puts your mind to work. As he told his Austin audience, “It’s a series of revelations and epiphanies for which the reader must connect the dots.”

While Hosseini set the story in specific countries, he grounded it in larger themes that cross borders and speak the language of the global family. He laid bare the fundamental elements of our common humanity.

Hosseini wrenched unexpected tears out of me in different sections, due not only to such universal refrains, but also because he assembled in the denouement a heartbreaking scenario similar to one I witnessed in my own family as well. Since I’ve never been fond of spoilers in reviews, I’ll not divulge the endgame of Mountains Echoed except to say it rang true.

Tears arising unbidden as I read usually alert me to the fact that I’m holding a compelling book in my hands—a “heads up” that I need to pay close attention to the illusion that I’m consuming a straightforward rendition of a simple tale.

Indeed, as some of Hosseini’s characters become Westernized in Mountains Echoed, I notice that an individualistic culture has slowly begun to muffle echoes of the earlier stages of their lives in a collectivistic society. The author writes with subtle strokes of his calligraphy brush to achieve this effect.

Perhaps such subtlety was intentional. After all, how clearly can we actually view an ancestor who lived several generations prior to our own and truly understand the choices made during that person’s sojourn on this planet?

Hosseini’s characters speak truths we ought to know like the backs of our hands already, and yet we continuously require reminding. Some of these verities underscore the values of memoir writing, genealogy research, and meditation. Hosseini prompts us to realize that it’s important to know where you came from, because in doing so you may encounter a part of yourself that was lost.

Gail Lumet Buckley, daughter of Lena Horne, wrote in her memoir titled The Hornes: An American Family: “Family faces are magic mirrors. Looking at people who belong to us, we see the past, present, and future. We make discoveries about ourselves and them.”

Flawed characters thwarted in love

Yet Hosseini denies most if not all of the characters in Mountains Echoed such types of discoveries due to assorted acts of separation he writes into their lives. He sets up many types of love in his characters’ relationships, and then creates formidable barriers to their perpetuation. Boston Globe columnist Ellen Goodman once wrote about herself: “This packrat has learned that what the next generation will value most is not what we owned, but the evidence of who we were and the tales of how we loved. In the end, it’s the family stories that are worth the storage.” The fictional individuals who people the Mountains Echoed plot won’t have such an inheritance, though. That’s where the angst in this novel arises, and it’s powerfully strong.

Hosseini in Austin.

“I really like flawed characters,” Hosseini told his Austin listeners. “They allow me the most to work with. All of us have things about ourselves that we don’t like at all. We can see our own flaws in them.”

He pointed out that the “evil stepmother” character, Parwana, “is the black sheep of her family“ but she “gets her day in the sun later in her own chapter.”

Fiction can be a potent tool. Authors who serve up their home countries via literature to the world can call attention to inequities, assist in cultural understanding, or play roles in uniting us. Consider such writers as Isabel Allende, Orhan Pamuk, or Chinua Achebe. And when a novelist writes about the assimilation of people from one culture into another culture, as such authors as Amy Tan or Junot Díaz or Jhumpa Lahiri have done, readers gain the perspectives of characters who have migrated from their native countries. In Mountains Echoed, Hosseini depicts the homelands of his characters (Afghanistan and Greece) as well as later adaptation to new countries (France and the United States), illustrating how Westernization has changed them.

What factors determine the impact of a literary contribution? Is it the words alone—or do timing, packaging, current news events, author talks explaining motivation and intent, and advance promotion each play a role? The Zeitgeist likely creates desire for certain subject matter. Once upon a time, journalists were taught the term Afghanistanism to avoid concentrating on issues in faraway places when problems in their own cities cried out for attention. Technology, transportation, and wars have both broadened our horizons and shrunk our world since that time, negating the term.

Hosseini mentioned the influence of the poet Rumi in his Austin talk, and he uses a wonderful Rumi quote as an epigraph in Mountains Echoed:

Out beyond ideas

of wrongdoing and rightdoing,

there is a field.

I’ll meet you there.

—Jelaluddin Rumi, 13th century

He also alluded to music in reference to his third novel: “My intention was that each chapter raises the stakes for what has happened before, creating a synchronicity—like a lot of single instruments playing together to create a symphony.”

Hosseini seems to have blended music, poetry, and myth in Mountains Echoed. An echo in music has a resonance that amplifies the sound and makes it reverberate with the underlying meaning. It’s a nice metaphor for what Hosseini accomplishes in his new novel.

There are hints of the Echo and Narcissus myth as well, if one focuses on the ideas of separation and later deprivation of speech and garbling of the tongue, as Juno did to Echo. The separation in Mountains Echoed deprived the siblings of speech with one another, and the novel’s ending symbolizes garbled memories.

The echo motif also fits into the storyline of Mountains Echoed as a rhetorical device, which Hosseini employs in both a literal and a figurative sense. With the repeated refrains and themes, one could almost view the novel as a musical composition of lyrical poetry, with a chorus continuing to sing praises to the nuclear family unit in the midst of a long narrative ballad, ideas John Hollander discusses in his book The Figure of Echo.

Hollander uses the example of echo in John Milton’s Paradise Lost, which indeed Afghanistan has become.

“The country is struggling with a lot of problems,” Hosseini said of his native land. “The big question is what will move into the vacuum when the US and NATO troops leave in 2014. There’s a lot of skepticism on the part of Afghans. Not many people in the West understand what the Afghans fear. The militia wars preceded the Taliban. Those were the darkest of the last thirty-two years. There’s a reason Afghanistan has been called ‘the graveyard of empires.’”

One audience member called out a heartfelt comment: “Thank you for teaching us about Afghanistan.”

BookPeople showed a five-minute film before Hosseini spoke, highlighting the Khaled Hosseini Foundation he has set up. The author explained how his organization concentrates on helping all the homeless refugees returning to Afghanistan by finding shelter for them there.

Hosseini’s shift from a medical career

“I was a doctor in my former life,” Hosseini said in his Texas book discussion. “I wrote all my life though,” he said. “I can’t remember a time when I didn’t love to write, but I didn’t think I was very good. I just did it for myself. I wrote Kite Runner, and then 9/11 happened. I felt the book would be distasteful at that time.” So he shelved it in the garage.

His wife ran across it “and made a bunch of notes on it. She urged me to try to publish it later.” He noted that she majored in rhetoric at UC Berkeley, and is his editor and a lawyer.

“She’s edited every draft. She can’t come up with an answer as to where the story should go,” he said, adding that “the danger of having an ‘in-house’ editor is that you don’t get what you need to hear—you get what you want to hear. Although sometimes she writes things like ‘LOL. You can’t be serious.’ I go into a mini funk when she does that.”

He sent Kite Runner around, but “it got rejected a lot.” Finally an agent (who is now deceased) took him on and Kite Runner was published. “I thought maybe my cousins would read it,” he joked. “I was still a doctor then.”

So just how did the transition from medicine to literature occur?

“Three things happened to change me from a doctor to a full-time writer,” he said, and listed them: “(1) I began to notice people reading my book on airplanes. (2) All my patients wanted to take up the time during their office visits asking me to sign their copies of my book. (3) I found myself as the answer to a ‘Jeopardy’ question when I was watching the show on TV. So I thought maybe I could take a year or so off.” The health plan he worked for “didn’t allow time off, so I had to quit to write.”

Listening to Hosseini articulate tales from his own family made me realize he’s a natural-born narrator. And the Mountains Echoed is a paean to the importance of storytelling to strengthen family bonds. There is an African saying: “When an elder dies, it is as if an entire library has burned to the ground.”

Writer Madeleine L’Engle once underscored this leitmotif when she said: “If you don’t recount your family history, it will be lost. Honor your own stories and tell them too. The tales may not seem very important, but they are what binds families and makes each of us who we are. ”

Every one of Hosseini’s three novels has seemed stronger than its predecessor to me, so I await the fourth with great expectations.

Lanie Tankard is a freelance writer and editor in Austin, Texas. A member of the National Book Critics Circle and former production editor of Contemporary Psychology: A Journal of Reviews, she has also been an editorial writer for the Florida Times-Union in Jacksonville. (Photo of Lanie Tankard and her grandmother by Toni Fuller. Photos of Khaled Hosseini by Elaine F. Tankard)